We talked with Professor Martin Fischer of Stanford University’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department in the run-up to WDBE. Our discussion covered what drew him to the discipline and the practical challenges of applying BIM in the modern built environment.

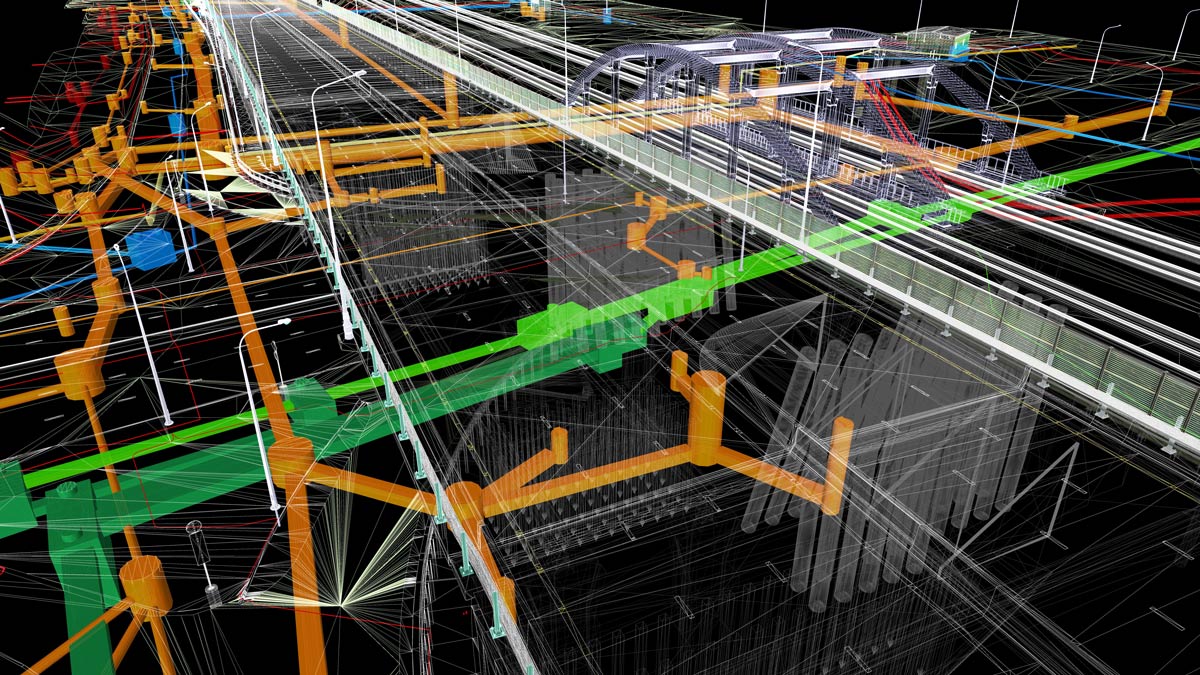

An essential part of contemporary design, Building Information Modelling (BIM) is a valuable collaborative practice when supported by the right suite of tools and workflows. It helps disparate teams work together, model progress on a build, and has been an area of interest for Professor Fischer since the start of his career.

Finding the right tool

Growing up in Switzerland, Professor Fischer’s father worked in the construction industry, with his son occasionally providing help over the weekends. Given a task to do one day “my father looked it over and said – it’s ok…but you could have done a better job if you’d used this particular tool,” says Prof. Fischer. “And I said – I know. He said – why the heck didn’t you? And I said – the tool was in the basement and getting it sounded like a lot of effort, I just decided to muddle through here. Then my father looked at me and said – you’re an idiot if you’re not using the best tool possible”.

This blunt critique stuck with him all the way through his pursuit of a career in civil engineering and the rise of modern information technology. BIM-adjacent tools have allowed practitioners to take advantage of design, technological, parametric, and simulation methodologies to develop insightful solutions on builds.

But convincing practitioners to adopt them as part of best practice is a different issue.

Application through necessity

Speaking about his early career, Prof. Fischer says that one of his first professional projects in the States was a large bridge in Rhode Island.

“I was stunned just how much time I and everyone in the office spent looking for the right information,” he says. “I thought…this is crazy. Sometimes I’d spend half my day trying to figure out what the latest version was and who was working from it. And then who had the right information, at which point, it was no longer up to date.”

Error and inefficiency have made waste a key concern for the modern built environment. BIM has been earmarked as a cost-effective, multi-purpose way to combat waste alongside optimizing a range of project elements.

Convinced there was a better way, and inspired by the work of researchers like Chuck Eastman, Prof. Fischer’s commitment to BIM was inspired in-part by Gehry’s El Peix, which was built from an onsite 3-D model in 1992. Here, theoretical innovation wasn’t a pressing concern.

“They just didn’t have time anymore,” Prof. Fischer explains. “They wanted this in place before the ’92 Olympics. But it would have required drawings, having workers interpret them, and risking misalignment between the architect and the builders. So, they had an architect on site with the 3-D model communicating directly with them. And I thought, that’s the future”.

Creating positive feedback

Prof. Fischer sees several benefits in BIM’s capacity to create what are known as positive feedback loops during a build and well beyond. This involves using a range of tools and approaches to capture data around how a building is designed, constructed, and utilized after completion.

These insights are then used to drive disciplinary change while also improving established information-gathering approaches; creating a virtuous cycle when implemented correctly.

“We got involved because a company got interested in trying out construction planning with Alice” says Prof. Fischer.

“We were able to create a parametric, detailed schedule at the level of each crane pick for the project. And while you can say ‘that’s crazy, that’s way too much detail’, the computer can handle the detail. Because we know that, without the right detail, any summary is useless. And a quality summary directly feeds into the strategy of construction.”

This capacity for continuous assessment and review is a key strength for the discipline. And for Prof. Fischer, the importance of digitization cannot be overstated.

“I would argue if you can’t make something digital, you cannot scale it across different people, processes, and parts of the organization. Because it’s going to be too much to communicate and be open to different interpretation,” he says. “What I’m excited about is digital feedback loops that are helping us really learn about what goes on in our buildings and infrastructure when they are built and how they are being used and then being operated”.

At the time, his team used Versatile Natures’ technology to capture all elements of crane picks for the project, then using the tool to map out a second project in California.

“For the first time, we got a record of every precast element on the job and compared it with our schedule,” says Prof. Fischer. “That’s a massive amount of data to sift through, but if you had the right method you could forecast how a project would go and manage resource allocation correctly. We have seen that we can reduce the error in predicting how the project will go quite significantly.”

Adjusting our approach

However, implementing these changes is far from easy. Prof. Fischer sees BIM as representing a ‘type of contract’ rather than prescriptive a set of tools, one that requires understanding and commitment from adopters. But in a conservative sector, making these changes can prove to be difficult.

“It’s actually a set of practices and behaviors. And that’s where a twofold challenge comes in,” explains Prof. Fischer.

“Firstly, it requires a kind of vulnerability that does not come easy to the kind of people that work in construction, because it works much better when you admit what you don’t know. And the other part is people being hung up on getting the best price”.

For him, there is a lack of holistic objectivity when it comes to planning. This produces an undue level of focus on cost and scheduling; leading the rest of the project to become ‘we’ll just do what we can’.

Committing to capturing good measurements, sustainability, and analysis helps give clients the best possible opportunity to get a design that suits their brief. Or, as Prof. Fischer puts it: “you get a much better shot at getting the kind of building you want rather one that just meets budget and schedule”.

What’s next?

At WDBE, Prof. Fischer’s content will focus on the importance of developing new methods, processes, and technologies. And changing the conversation around implementation.

“First we’ve got to have trust,” he says. “Then we bring the tools to create a symbiotic relationship that strengthens that trust. Which in turn helps create better tools, which helps us use them better.

“It’s like the difference between using paper maps and the navigation app on your smartphone. People are initially hesitant, but it very quickly becomes – oh, ok… why would I use paper maps anymore? There used to be a lot of steps and work involved. But now that’s all gone and replaced with a new viewpoint. And it’s one that gets us building a better solution together.”

Professor Martin Fischer will be speaking at WDBE 2020 on September 30, 2020. You can book tickets at wdbe.org or learn more about the other events and the regularly updated agenda.

This article was first published at wdbe.org

Responses